Friday, April 13, 2012

Ever since I was a child I was interested in the Titanic. I was always a disaster movie queen I guess. Prior to the last Titanic craze in 1998, I researched and wrote biographies for the website Encyclopedia Titanica (which seems to be having problems lately).

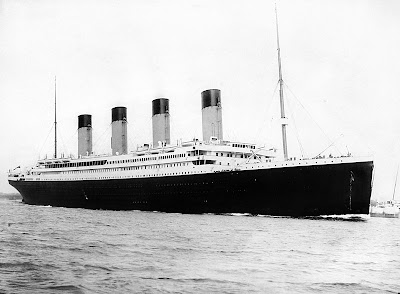

Titanic.

Recently I decided to prepare an undated entry for one of the passengers and chose a man who had a truly remarkable escape. The article I submitted to the website is below.

George Alexander Lucien Rheims was born on 6 January 1879 in New York City, New York, the son of Leon Rheims and Jeanette Kearns. His father was a French native who came to the United States in the late 1850s, while his mother was a New York native, born to French immigrant parents, they were married on 25 October 1867 in Brooklyn. On 1 June 1880, George’s parents and siblings- Rosalie (later Comtesse de Roussy de Sales), Gaston, Charles, Leon Jr., and Henry lived at 4 E. 30th Street in New York City. His father owned a millinery goods business and was quite wealthy, the family employed eight female servants.

George’s family often returned to France, and he lived there between 1883 and 1887. In January 1892, the family millinery import business suffered a tremendous loss when a fire occurred at numbers 5 through 9 in Union Square. Leon Rheims had between $200,000 and $250,000 in goods that were destroyed. The next month, an auction of the remaining stock, which included ostrich feathers, trimmings, plushes, and Florentine silks, was held. Afterward, George’s parents returned to Paris, although the Rheims millinery business continued, with stores in Paris, Boston, and New York City.

George’s father died in Paris on 31 January 1894, leaving an estate valued between $300,000 to $400,000 to his wife, with the five children to receive it after her death.

George returned to France and lived there for much of the time afterward, returning briefly to the United States in 1900 and 1905-1906. Passenger records list George Rheims arriving in the United States on numerous occasions, probably visiting family members and working at the family business. On 7 April 1906, George arrived in New York City after sailing on 31 March 1906 from Le Havre aboard the S. S. La Lorraine. He was working as a merchant and was “on a visit to the States.” On 5 October 1907, George and his brother Gaston Richard Rheims arrived about La Provence that had sailed from Le Havre on 28 September 1907. On 2 February 1910, George arrived in New York City on the Kaiser Wilhelm Der Grosse. He was listed as an importer. On 26 February 1911, he returned from Cherbourg, France aboard the Amerika. On 21 October 1911, George and a brother (whose name is illegible) arrived on La Provence from Havre.

George was married in late 1911 or early 1912 to Marie Lamoine Loring. Marie was born on 21 September 1880 in Chicago, Illinois, daughter of Francis L. Loring and Williamana Holland. Her parents reportedly refused to accept Rheims. There is the likelihood that George was Jewish, and this may have been the causal factor (It appears that George's brother Leon was in France during World War II was executed by the Nazis for being Jewish)..

Marie Loring Rheims, passport photo from 1915.

George was living at 42 Rue de Paradis in Paris at the time he boarded the Titanic at Cherbourg with his brother-in-law, Joseph Holland Loring, on a voyage to New York City. He paid 39 pounds and 12 shillings for ticket 17604. The two men had adjoining staterooms on B deck. On the night of April 15th, George and Joseph were in the smoking room “trying to figure out the speed of the boat to see what the run would be the next day. Then the steward, whom I think they called the commodore steward, because I think he is the oldest steward, came up to us and said we might figure on a bigger run. We said, ‘Why?’ He answered, ‘Because we are making faster speed than we were yesterday.’ My brother-in-law said, ‘What do you know about it?’ He said, ‘I got it from the engine room.’ My brother-in-law said, ‘That don’t mean anything.’ He said, ‘Gentlemen, come out and see for yourself.” We went out in the passage hallway right outside of the smoking room and we stood there, and he said, ‘You notice that the vibration of the boat is much greater tonight than it has ever been.’ And we did notice the vibration, which was very strong that night, and my brother-in-law, whose stateroom was right underneath the passage, said, ‘I never noticed this vibration before; we are evidently making very good speed.”

After the collision with the iceberg, George said “no one seemed to know for twenty minutes after the boat struck that anything had happened. Many of the passengers stood round for an hour with their life belts on, he said, and saw people getting into the boats.” Rheims ran down to his stateroom and grabbed a picture of his wife from a frame. When he returned to deck, he and Loring stripped off their heavy clothing and prepared to enter the water towards the bow. Loring hesitated, considering heading to the stern. Rheims, in a letter he wrote to his wife afterward, claimed that he saw an officer commit suicide after announcing, “Gentlemen, each man for himself. Good-bye.”

In the pandemonium, as the Titanic’s bow dipped under, Rheims and Loring were separated and Rheims ended up near Collapsible Boat A. He later said that he shook hands with his brother-in-law, who would not jump, and leaped over the side of the boat. He swam for a quarter of an hour and reached a boat, with 18 occupants, half under water. The people were in water up to their knees. Seven of them, he said, died during the night.” Before crawling into the boat, Rheims had had to untangle himself from some deck chairs and a mass of rope. Another survivor in Collapsible Boat A would say that they saw Rheims standing in the boat in his underwear. Rheims later said he had to take charge of the boat, and that the occupants of Collapsible Boat A had to prevent additional people from climbing aboard. The 20 or so survivors aboard used pieces of boards to paddle away from the mass of people struggling in the water. On the initial survivor lists, telegraphed to shore, he was listed as “Mrs. George Rheims.” Afterward, some people would think he escaped the Titanic dressed as a woman.

George’s wife Marie was pregnant at the time of the disaster, and subsequently gave birth to their son George Loring Rheims on 29 July 1912 in Paris. In early 1913, George was one of many passengers who filed claims with the United States Commissioner Gilchrist. George reported that he “was on a submerged, defective collapsible lifeboat for hours, he says, and for shock and anguish, he demands $10,700; for baggage, $6418.” Among the items he claimed he lost were a turquoise scarf pin, a fur coat, eight suits of clothes, a fur rug, an umbrella, and 48 shirts.

George returned to live in France afterward. He, wife Maria, and son Loring returned to New York City on 16 October 1914 aboard the Mauretania. On 1 October 1901, George and Marie arrived in New York City from Liverpool, England aboard the St. Paul. George frequently traveled abroad for business, with passport applications existing for 1914, 1915, 1917, 1918, and 1920. These provide biographical information, as well as physical descriptions (and in some cases blurry photographs (e.g., 1915 and 1920)). As an example, he applied for a passport in December 1915. He reported that he was 5 ft 11 inches tall, had a broad forehead, brown eyes, a straight nose, a medium mouth, a round chin, very dark brown hair (balding by 1920), a ruddy complexion, and a round face. He noted that he was employed by the Leon Rheims Company, Importers, at 417 5th Avenue in New York City and that he and his wife were traveling to France and England for the importing business. By June 1917, the company was renamed George Rheims & Cie. and George was living in Paris, occasionally visiting England on business. He left the United States again in March 1918, arriving in France on 5 April 1918. In November 1918, he applied for a temporary permit to visit Switzerland while residing in France. George arrived on 1 January 1919 aboard the S. S. Espagne, leaving Bordeau, France on 21 December 1918.

br />

In November 1930, George attended a luncheon at the Olympic Hotel in Seattle. His wife attended a luncheon in Seattle in January 1931. In 1936, the couple lived in Pasadena, California. They frequently traveled back and forth between Pasadena and Seattle. As war began on the European continent, George, Maria, and their son George returned to the United States from Lisbon, Portugal on 18 October 1940 aboard the Exeter.

During World War II, George and Marie’s son George enlisted at Fort Dix, New Jersey on 14 March 1942. He was single at the time and reported that he had attended college for four years. He served as a Captain in the Headquarters of the 2nd Infantry Division during the war. After his death on 11 June 1964, he would be buried in Arlington National Cemetery in Washington, D.C. George was required to register for the draft in the World War II in 1942. At that time he was retired and was living in the Exeter Hotel in Seattle, Washington. In 1945, his sister, “Countess J. de Roussy de Sales,” visited Seattle and stayed with George and his wife. She had fled France during the war as a refugee and was known for her work with the French Red Cross. The following year saw a visit from the couple’s son George, his French wife Anne, and their son, George III. George’s sister Lily died in October 1948.

In February 1950, George and Marie sold the Exeter Hotel and moved to Biarritz, France. Marie died there on 8 August 1954. She left behind an estate valued at over $100,000. George was later married to Dolores Maria Josefa Lolita Candela in Biarritz. He died there on 1 March 1963 from myocardial infarction with pulmonary oedemia. He was buried in plot #76-1892 in the Passy’s Cemetery in Paris. He left his Seattle properties, valued at over $400,000 to his wife and grandson George Loring Rheims, with smaller bequests to his nephew Richard de Roussy de Sales and three Seattle friends.

Titanic.

Recently I decided to prepare an undated entry for one of the passengers and chose a man who had a truly remarkable escape. The article I submitted to the website is below.

George Alexander Lucien Rheims was born on 6 January 1879 in New York City, New York, the son of Leon Rheims and Jeanette Kearns. His father was a French native who came to the United States in the late 1850s, while his mother was a New York native, born to French immigrant parents, they were married on 25 October 1867 in Brooklyn. On 1 June 1880, George’s parents and siblings- Rosalie (later Comtesse de Roussy de Sales), Gaston, Charles, Leon Jr., and Henry lived at 4 E. 30th Street in New York City. His father owned a millinery goods business and was quite wealthy, the family employed eight female servants.

George’s family often returned to France, and he lived there between 1883 and 1887. In January 1892, the family millinery import business suffered a tremendous loss when a fire occurred at numbers 5 through 9 in Union Square. Leon Rheims had between $200,000 and $250,000 in goods that were destroyed. The next month, an auction of the remaining stock, which included ostrich feathers, trimmings, plushes, and Florentine silks, was held. Afterward, George’s parents returned to Paris, although the Rheims millinery business continued, with stores in Paris, Boston, and New York City.

George’s father died in Paris on 31 January 1894, leaving an estate valued between $300,000 to $400,000 to his wife, with the five children to receive it after her death.

George returned to France and lived there for much of the time afterward, returning briefly to the United States in 1900 and 1905-1906. Passenger records list George Rheims arriving in the United States on numerous occasions, probably visiting family members and working at the family business. On 7 April 1906, George arrived in New York City after sailing on 31 March 1906 from Le Havre aboard the S. S. La Lorraine. He was working as a merchant and was “on a visit to the States.” On 5 October 1907, George and his brother Gaston Richard Rheims arrived about La Provence that had sailed from Le Havre on 28 September 1907. On 2 February 1910, George arrived in New York City on the Kaiser Wilhelm Der Grosse. He was listed as an importer. On 26 February 1911, he returned from Cherbourg, France aboard the Amerika. On 21 October 1911, George and a brother (whose name is illegible) arrived on La Provence from Havre.

George was married in late 1911 or early 1912 to Marie Lamoine Loring. Marie was born on 21 September 1880 in Chicago, Illinois, daughter of Francis L. Loring and Williamana Holland. Her parents reportedly refused to accept Rheims. There is the likelihood that George was Jewish, and this may have been the causal factor (It appears that George's brother Leon was in France during World War II was executed by the Nazis for being Jewish)..

Marie Loring Rheims, passport photo from 1915.

George was living at 42 Rue de Paradis in Paris at the time he boarded the Titanic at Cherbourg with his brother-in-law, Joseph Holland Loring, on a voyage to New York City. He paid 39 pounds and 12 shillings for ticket 17604. The two men had adjoining staterooms on B deck. On the night of April 15th, George and Joseph were in the smoking room “trying to figure out the speed of the boat to see what the run would be the next day. Then the steward, whom I think they called the commodore steward, because I think he is the oldest steward, came up to us and said we might figure on a bigger run. We said, ‘Why?’ He answered, ‘Because we are making faster speed than we were yesterday.’ My brother-in-law said, ‘What do you know about it?’ He said, ‘I got it from the engine room.’ My brother-in-law said, ‘That don’t mean anything.’ He said, ‘Gentlemen, come out and see for yourself.” We went out in the passage hallway right outside of the smoking room and we stood there, and he said, ‘You notice that the vibration of the boat is much greater tonight than it has ever been.’ And we did notice the vibration, which was very strong that night, and my brother-in-law, whose stateroom was right underneath the passage, said, ‘I never noticed this vibration before; we are evidently making very good speed.”

After the collision with the iceberg, George said “no one seemed to know for twenty minutes after the boat struck that anything had happened. Many of the passengers stood round for an hour with their life belts on, he said, and saw people getting into the boats.” Rheims ran down to his stateroom and grabbed a picture of his wife from a frame. When he returned to deck, he and Loring stripped off their heavy clothing and prepared to enter the water towards the bow. Loring hesitated, considering heading to the stern. Rheims, in a letter he wrote to his wife afterward, claimed that he saw an officer commit suicide after announcing, “Gentlemen, each man for himself. Good-bye.”

In the pandemonium, as the Titanic’s bow dipped under, Rheims and Loring were separated and Rheims ended up near Collapsible Boat A. He later said that he shook hands with his brother-in-law, who would not jump, and leaped over the side of the boat. He swam for a quarter of an hour and reached a boat, with 18 occupants, half under water. The people were in water up to their knees. Seven of them, he said, died during the night.” Before crawling into the boat, Rheims had had to untangle himself from some deck chairs and a mass of rope. Another survivor in Collapsible Boat A would say that they saw Rheims standing in the boat in his underwear. Rheims later said he had to take charge of the boat, and that the occupants of Collapsible Boat A had to prevent additional people from climbing aboard. The 20 or so survivors aboard used pieces of boards to paddle away from the mass of people struggling in the water. On the initial survivor lists, telegraphed to shore, he was listed as “Mrs. George Rheims.” Afterward, some people would think he escaped the Titanic dressed as a woman.

George’s wife Marie was pregnant at the time of the disaster, and subsequently gave birth to their son George Loring Rheims on 29 July 1912 in Paris. In early 1913, George was one of many passengers who filed claims with the United States Commissioner Gilchrist. George reported that he “was on a submerged, defective collapsible lifeboat for hours, he says, and for shock and anguish, he demands $10,700; for baggage, $6418.” Among the items he claimed he lost were a turquoise scarf pin, a fur coat, eight suits of clothes, a fur rug, an umbrella, and 48 shirts.

George returned to live in France afterward. He, wife Maria, and son Loring returned to New York City on 16 October 1914 aboard the Mauretania. On 1 October 1901, George and Marie arrived in New York City from Liverpool, England aboard the St. Paul. George frequently traveled abroad for business, with passport applications existing for 1914, 1915, 1917, 1918, and 1920. These provide biographical information, as well as physical descriptions (and in some cases blurry photographs (e.g., 1915 and 1920)). As an example, he applied for a passport in December 1915. He reported that he was 5 ft 11 inches tall, had a broad forehead, brown eyes, a straight nose, a medium mouth, a round chin, very dark brown hair (balding by 1920), a ruddy complexion, and a round face. He noted that he was employed by the Leon Rheims Company, Importers, at 417 5th Avenue in New York City and that he and his wife were traveling to France and England for the importing business. By June 1917, the company was renamed George Rheims & Cie. and George was living in Paris, occasionally visiting England on business. He left the United States again in March 1918, arriving in France on 5 April 1918. In November 1918, he applied for a temporary permit to visit Switzerland while residing in France. George arrived on 1 January 1919 aboard the S. S. Espagne, leaving Bordeau, France on 21 December 1918.

br />

George Rheims, 1923 passport photo.

In November 1930, George attended a luncheon at the Olympic Hotel in Seattle. His wife attended a luncheon in Seattle in January 1931. In 1936, the couple lived in Pasadena, California. They frequently traveled back and forth between Pasadena and Seattle. As war began on the European continent, George, Maria, and their son George returned to the United States from Lisbon, Portugal on 18 October 1940 aboard the Exeter.

During World War II, George and Marie’s son George enlisted at Fort Dix, New Jersey on 14 March 1942. He was single at the time and reported that he had attended college for four years. He served as a Captain in the Headquarters of the 2nd Infantry Division during the war. After his death on 11 June 1964, he would be buried in Arlington National Cemetery in Washington, D.C. George was required to register for the draft in the World War II in 1942. At that time he was retired and was living in the Exeter Hotel in Seattle, Washington. In 1945, his sister, “Countess J. de Roussy de Sales,” visited Seattle and stayed with George and his wife. She had fled France during the war as a refugee and was known for her work with the French Red Cross. The following year saw a visit from the couple’s son George, his French wife Anne, and their son, George III. George’s sister Lily died in October 1948.

In February 1950, George and Marie sold the Exeter Hotel and moved to Biarritz, France. Marie died there on 8 August 1954. She left behind an estate valued at over $100,000. George was later married to Dolores Maria Josefa Lolita Candela in Biarritz. He died there on 1 March 1963 from myocardial infarction with pulmonary oedemia. He was buried in plot #76-1892 in the Passy’s Cemetery in Paris. He left his Seattle properties, valued at over $400,000 to his wife and grandson George Loring Rheims, with smaller bequests to his nephew Richard de Roussy de Sales and three Seattle friends.